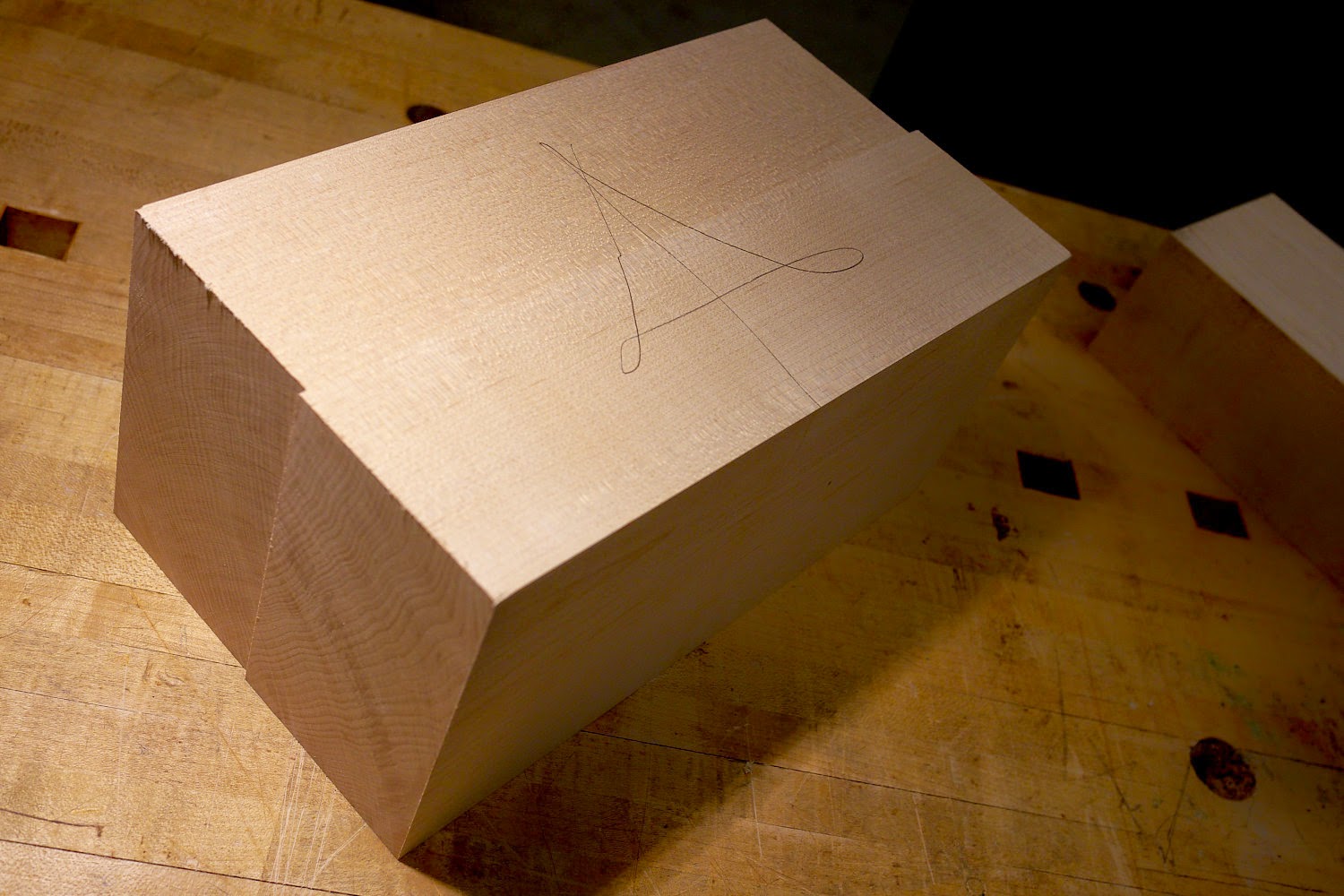

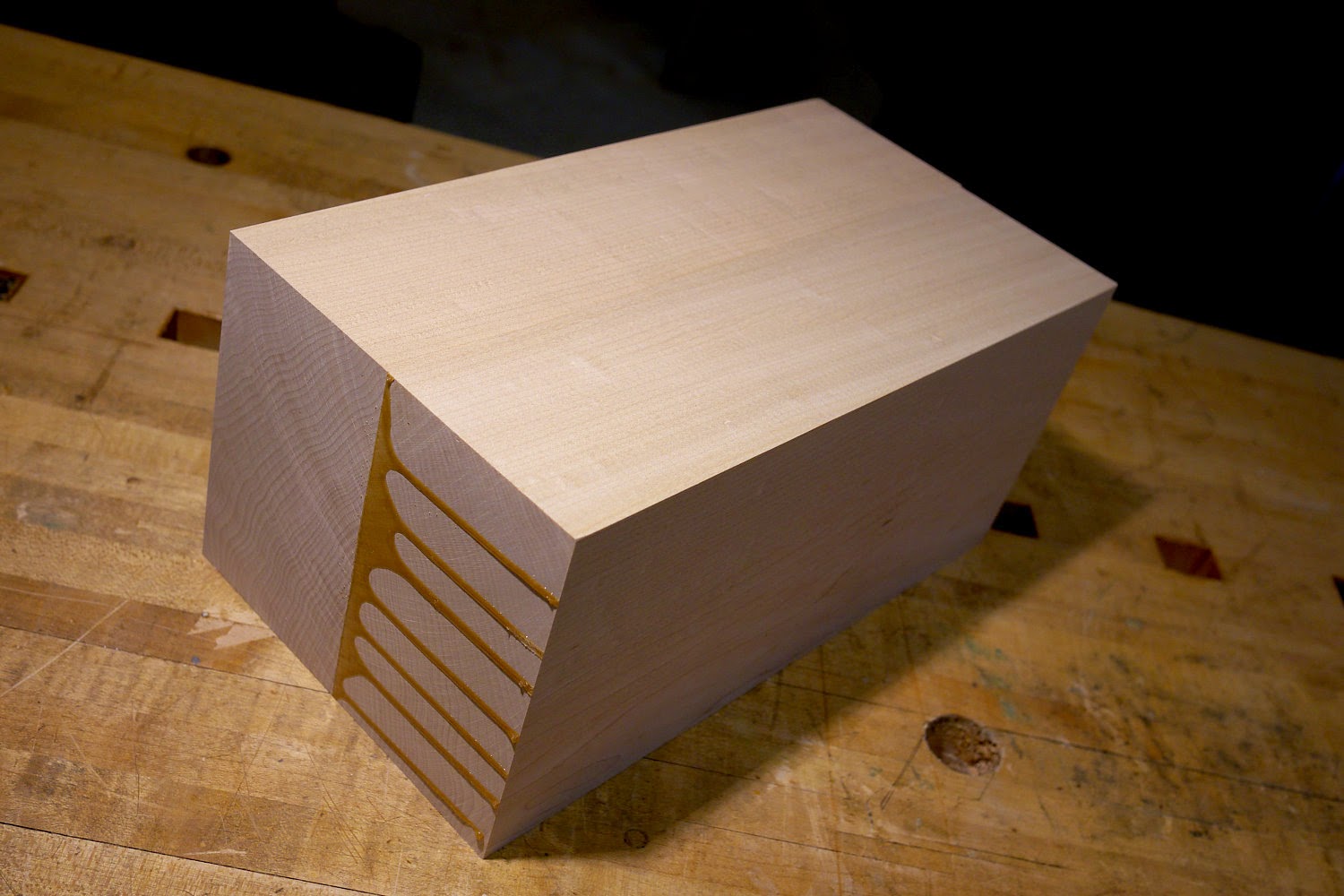

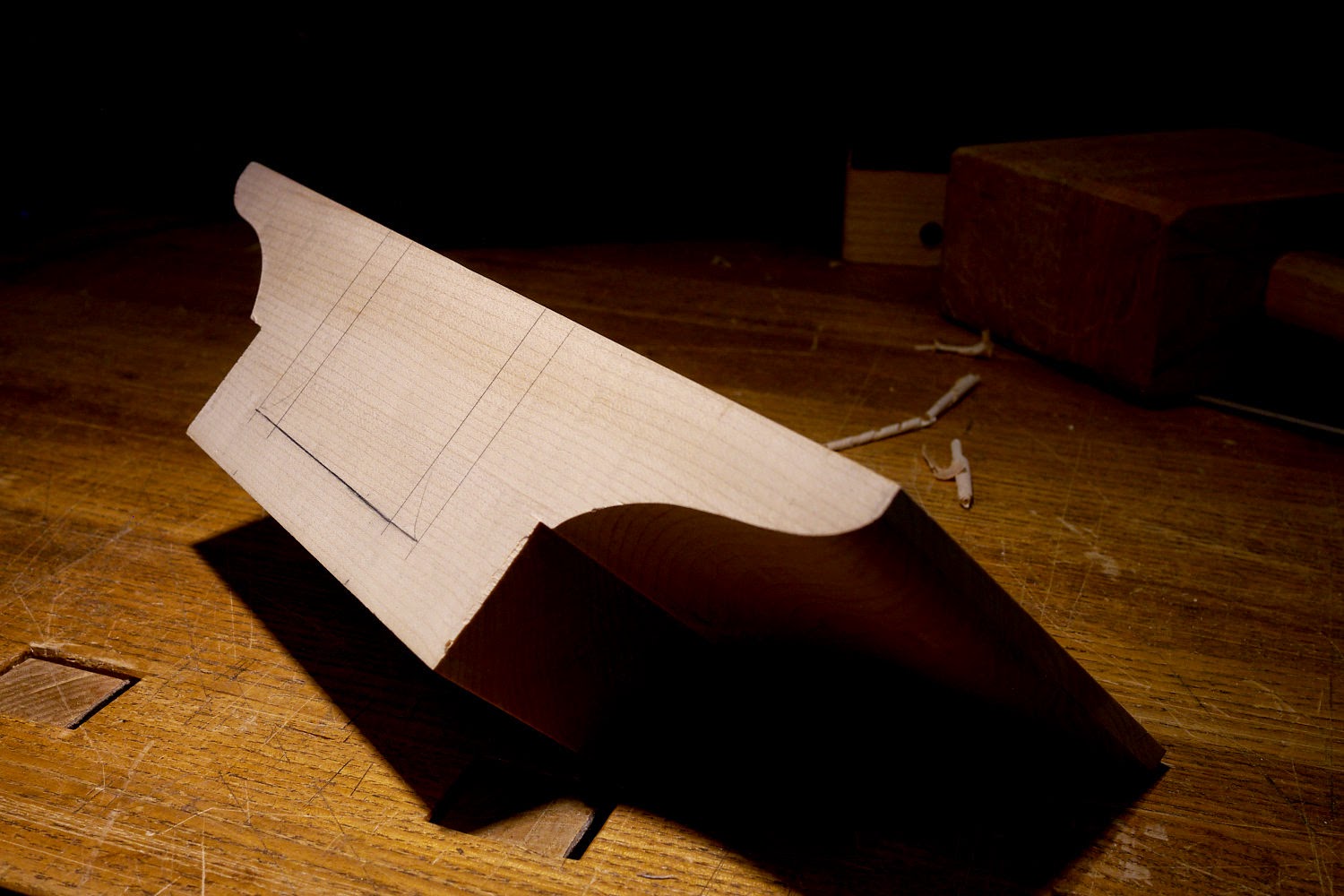

This morning I cut the assembled body to final length and laid out the final width as well as the main 45 degree chamfer. I won't cut the waste sections off until later.

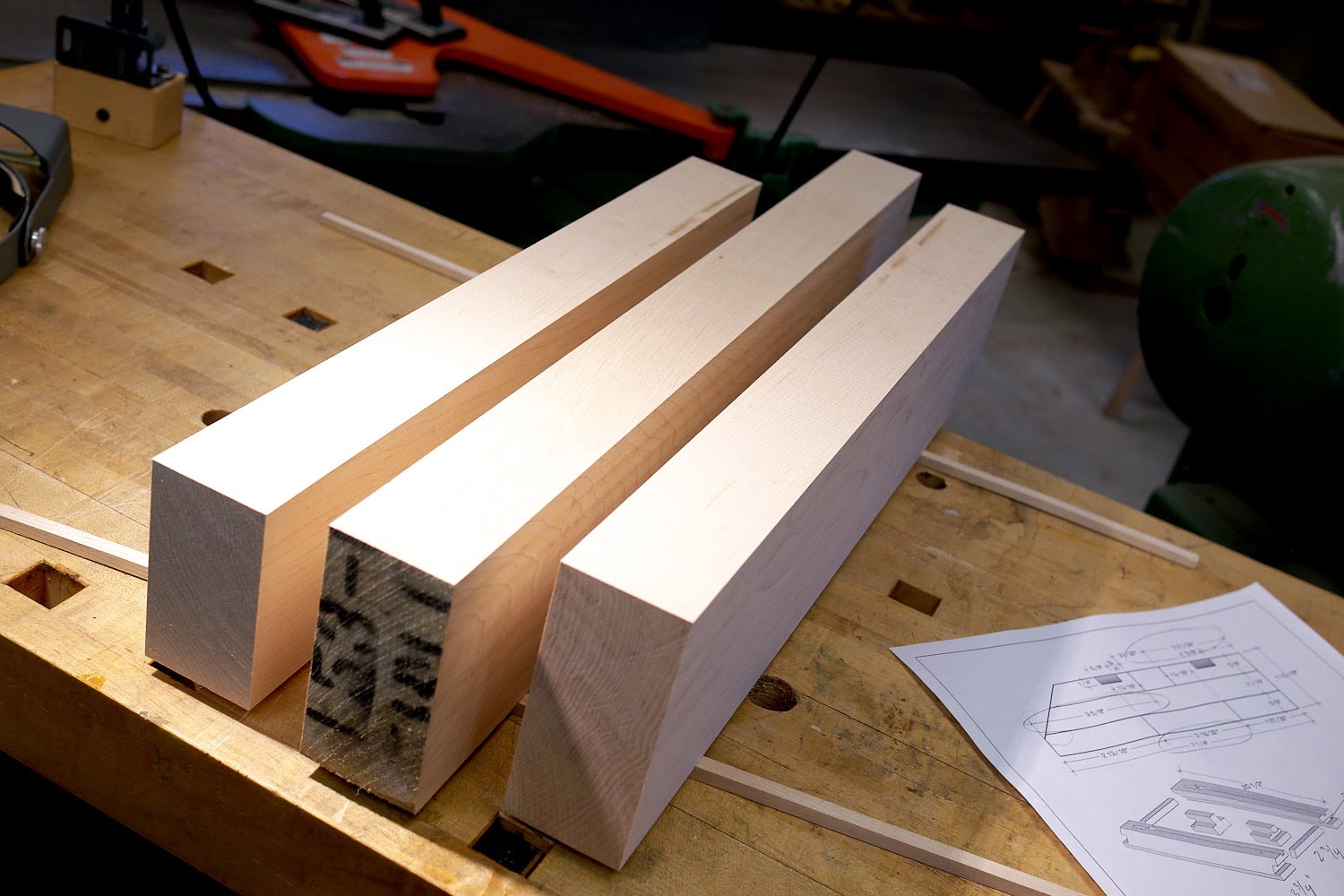

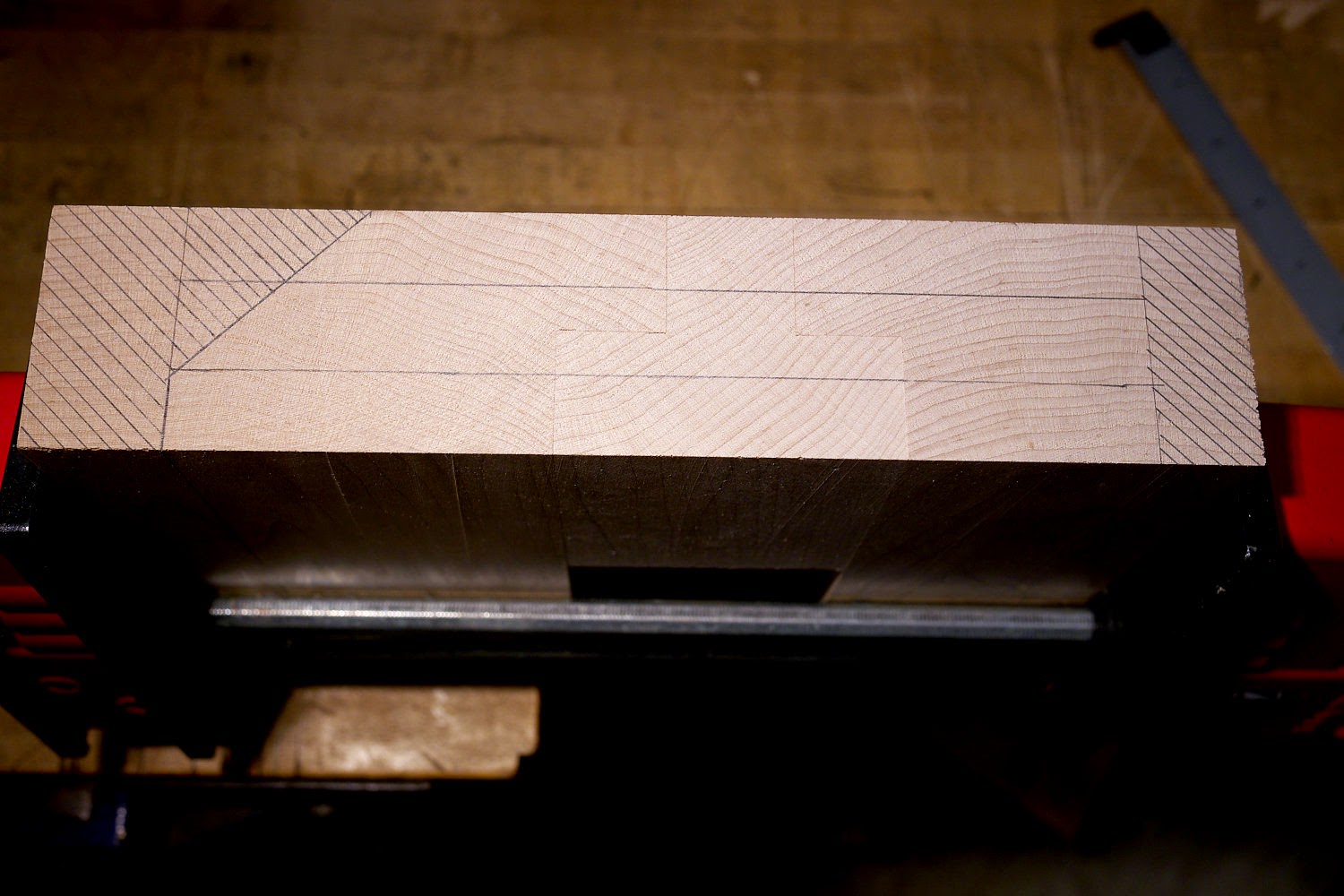

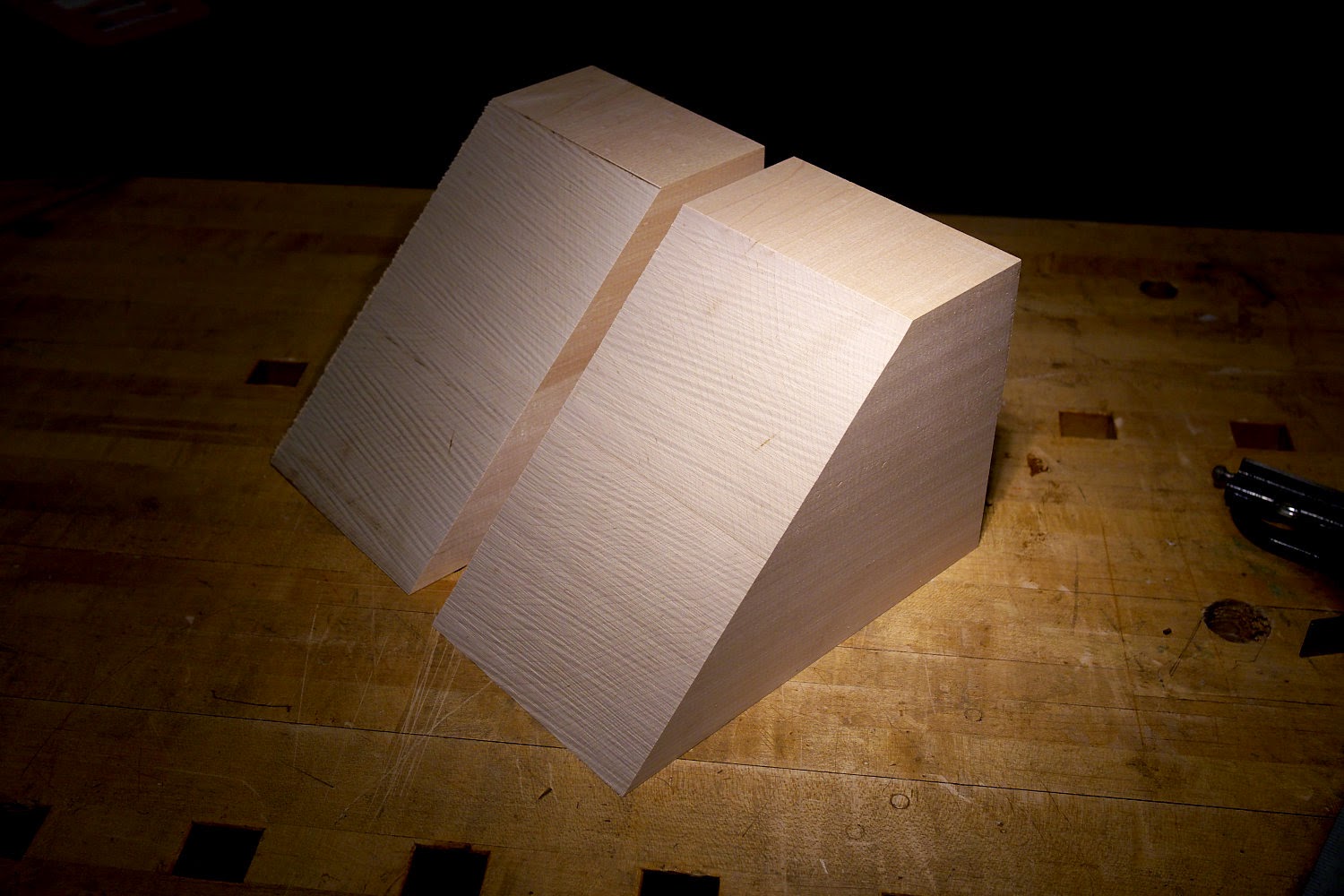

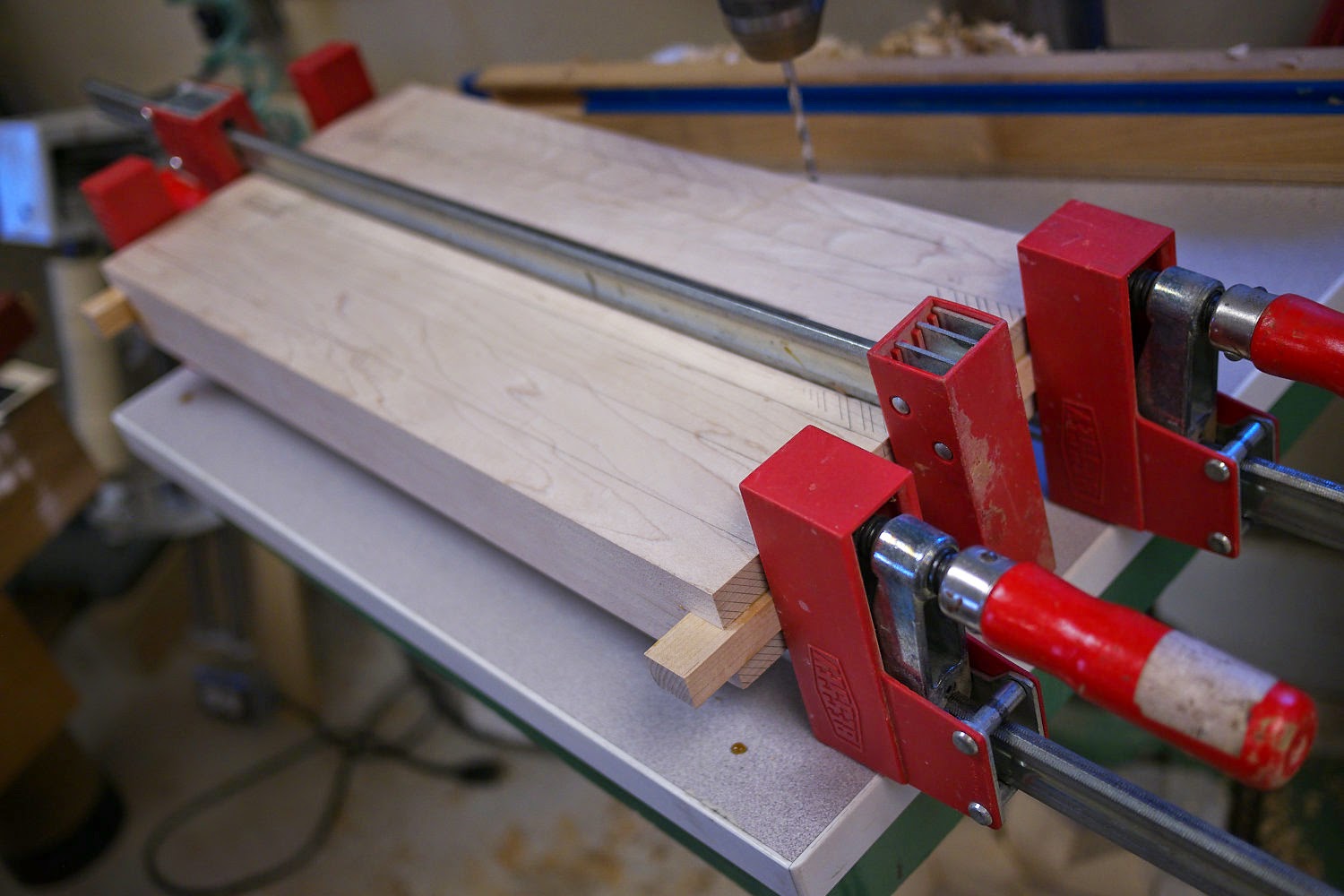

I took the jaw blank out of the clamps and four squared it. I milled it to 4-13/16" wide (the width of the wider, fixed jaw) by 5-9/16" tall. Don't confuse the nut block in the drawing above for the jaws. I didn't include the jaws in this drawing. I then sawed the blank in half at 45 degrees on the band saw. Each jaw is overlength by an inch or so. I'll cut them to final size after all the joinery is done and the vise is working smoothly.

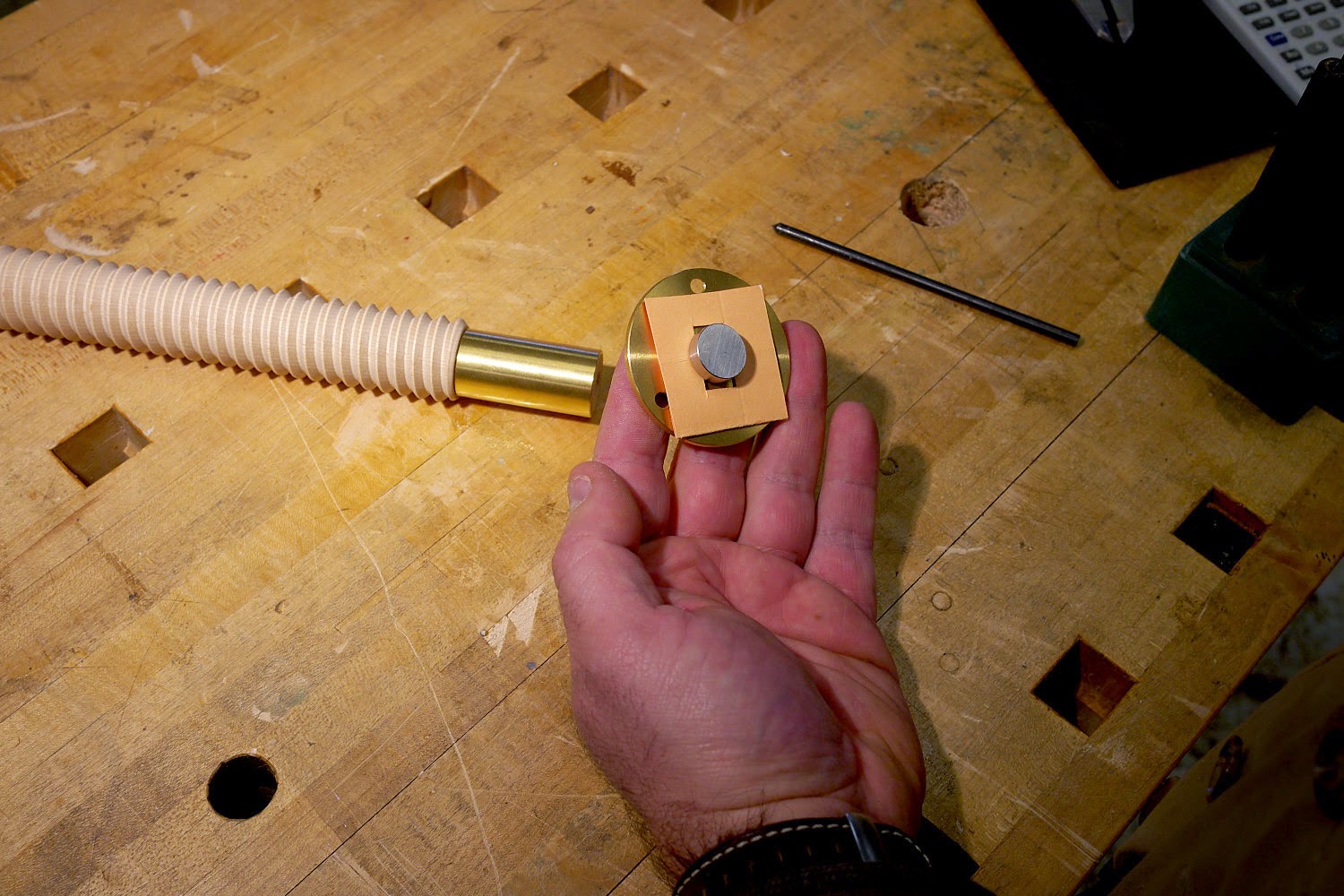

To install the garter you'll need to make a small drilling block. But first you'll need to find the location of the groove pin which holds the ferrule and garter pin in place.

The garter must be somewhat loose on the garter pin so the screw is free to turn easily. To achieve that loose fit, we need to position the groove pin in the right place.

Cut a shim that's about 20 thousands thick. I made mine from a double layer of paper cut from a file folder. Place this shim between the garter and the garter pin.

With the ferrule on the screw's tenon, press the garter and garter pin flat to the end of the screw.

Using a transfer punch (or a 3/16" bradpoint bit) insert it into the hole in the garter pin and mark the brass ferrule. Don't tap it with a hammer, just press by hand. The soft brass will mark easily.

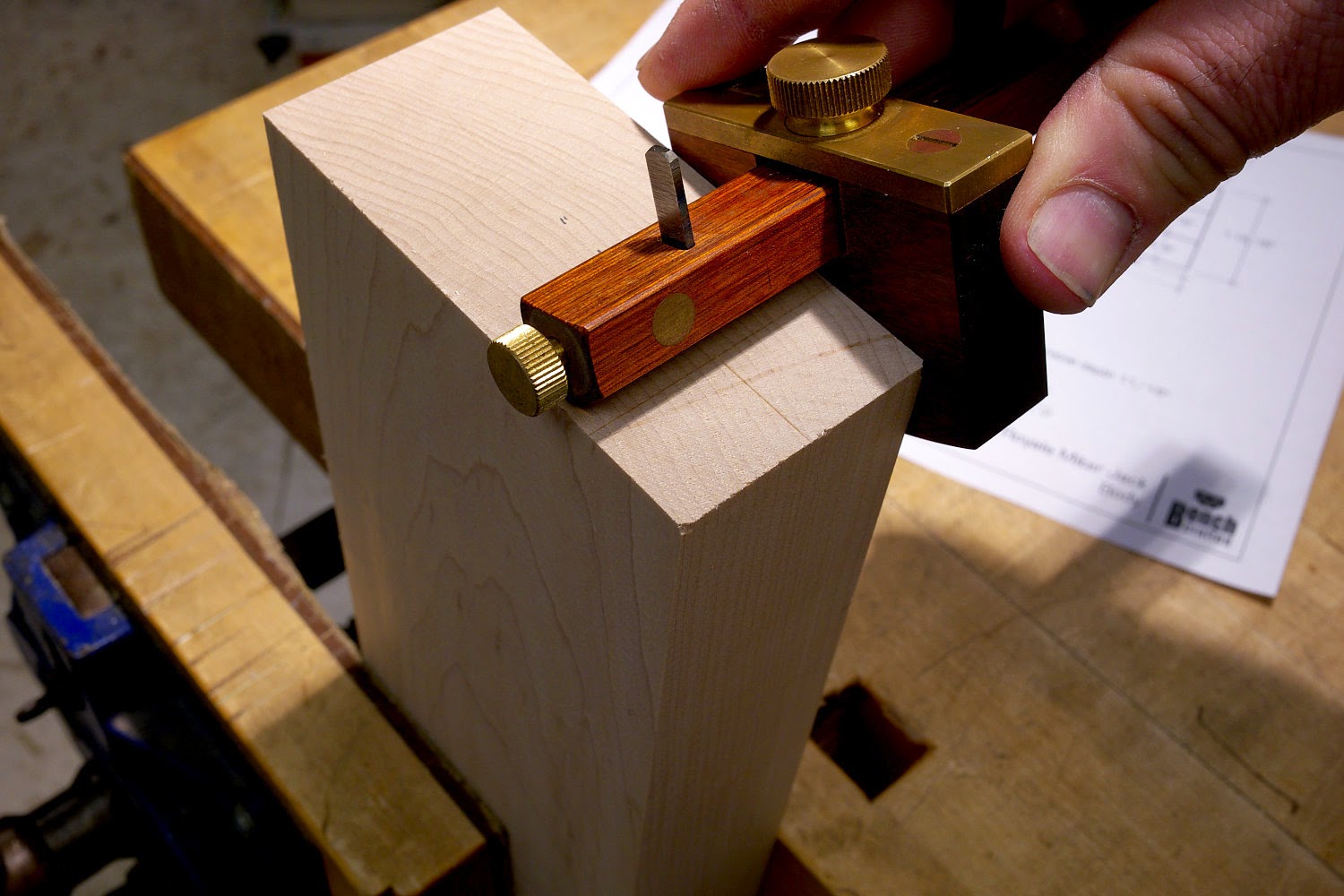

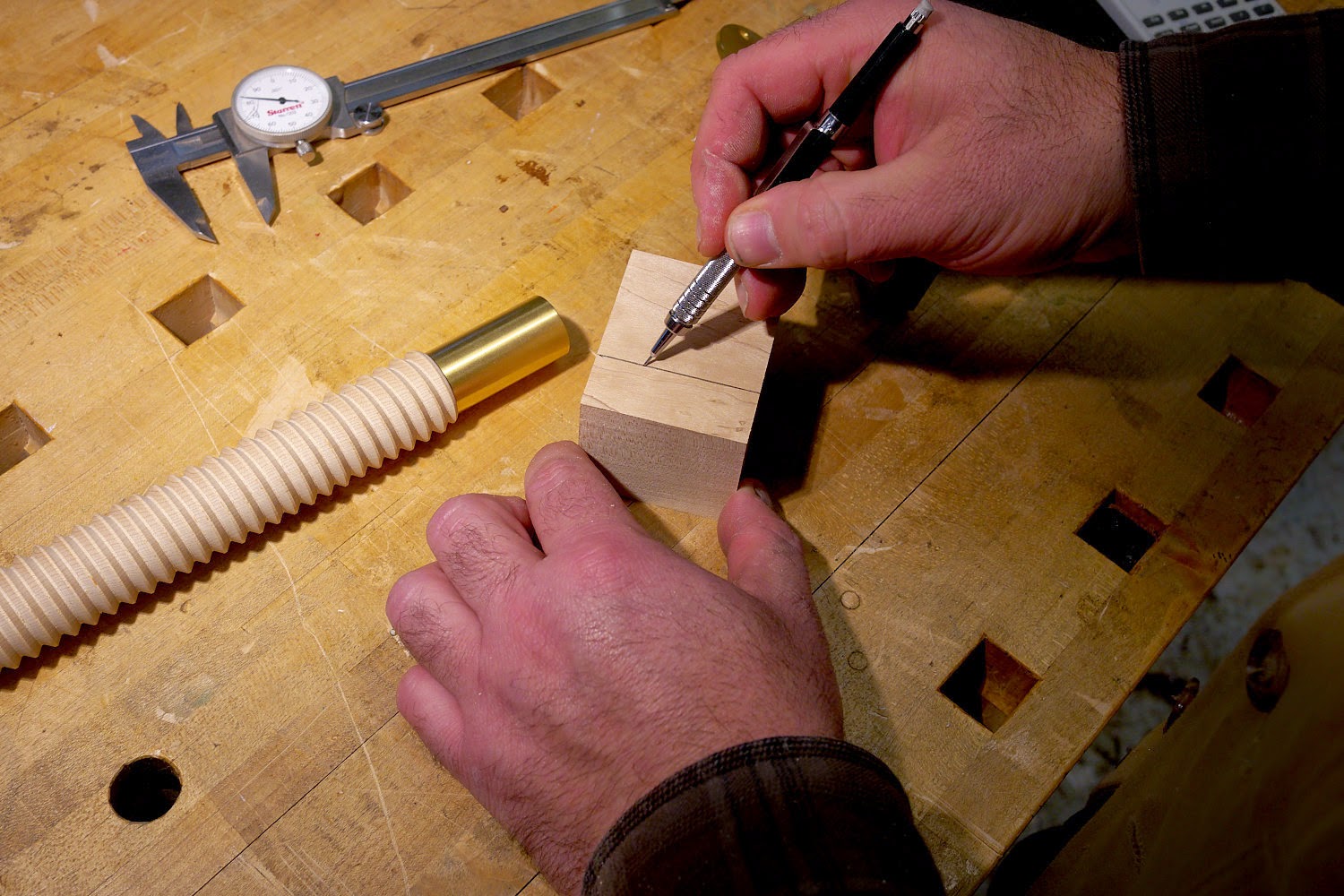

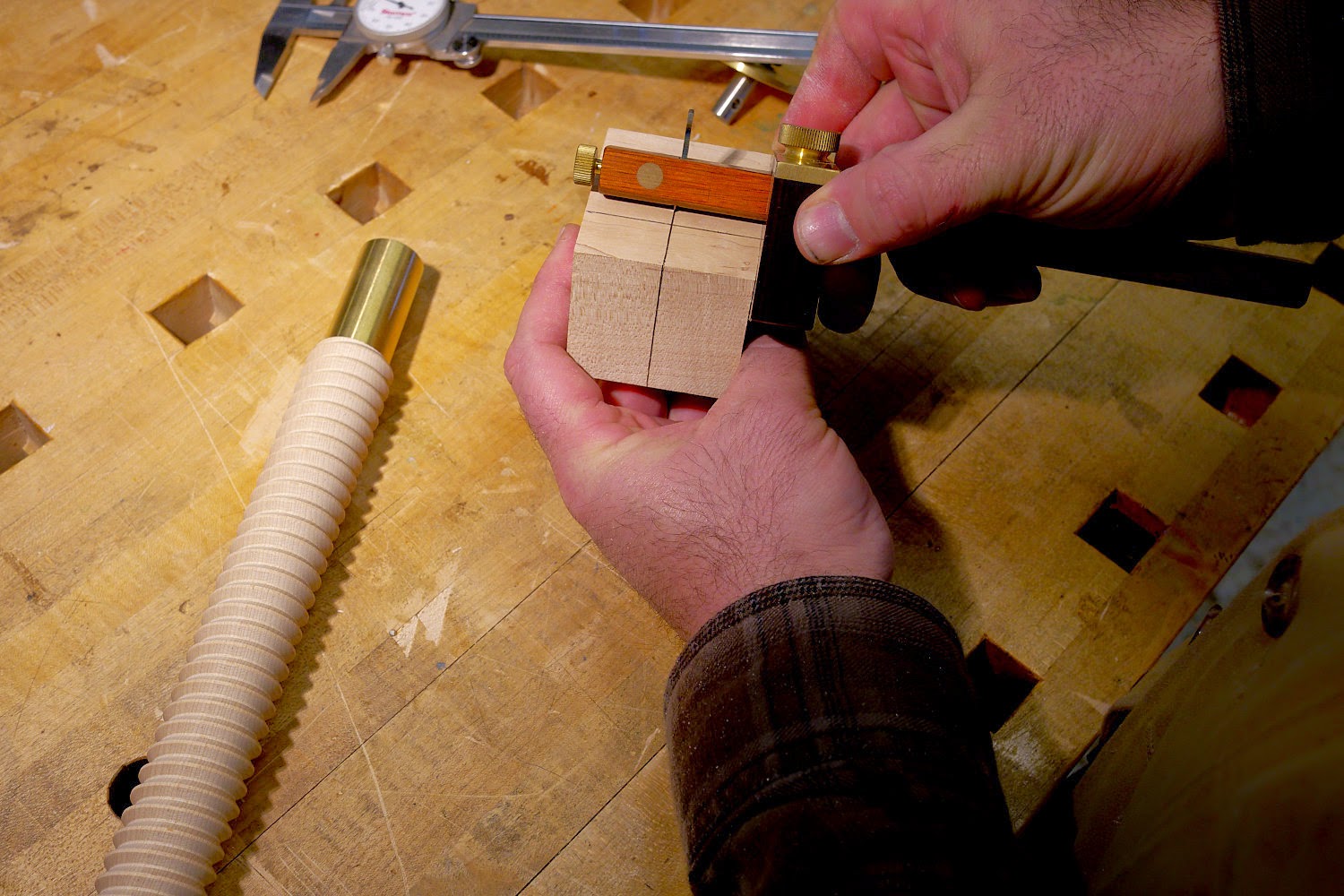

Remove the garter pin and set a marking gauge so the scribe touches the mark you made.

Get a scrap of wood that's true. The size is not important. Just make sure its about 1/2" wider than the length of the screw's tenon. Using the marking gauge, scribe a line across the top of the block. I'm pinching the end grain here with my left hand. I'm darkening the scribe line with a pencil. This is the location of the 3/16" cross hole.

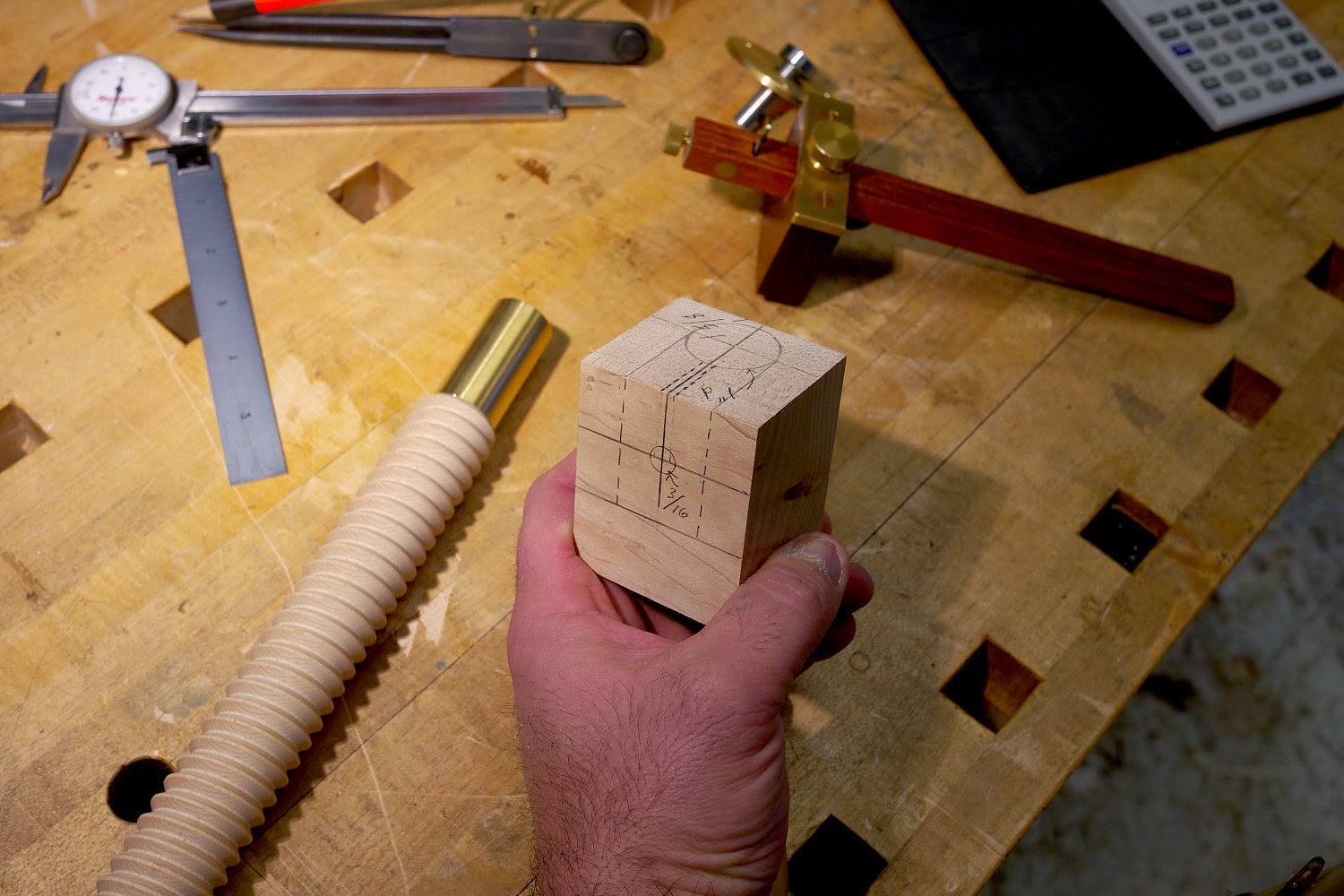

Reset your marking gauge for exactly twice the previous setting and scribe another line parallel to the previous one. This will be the depth of the hole the screw's tenon fits into.

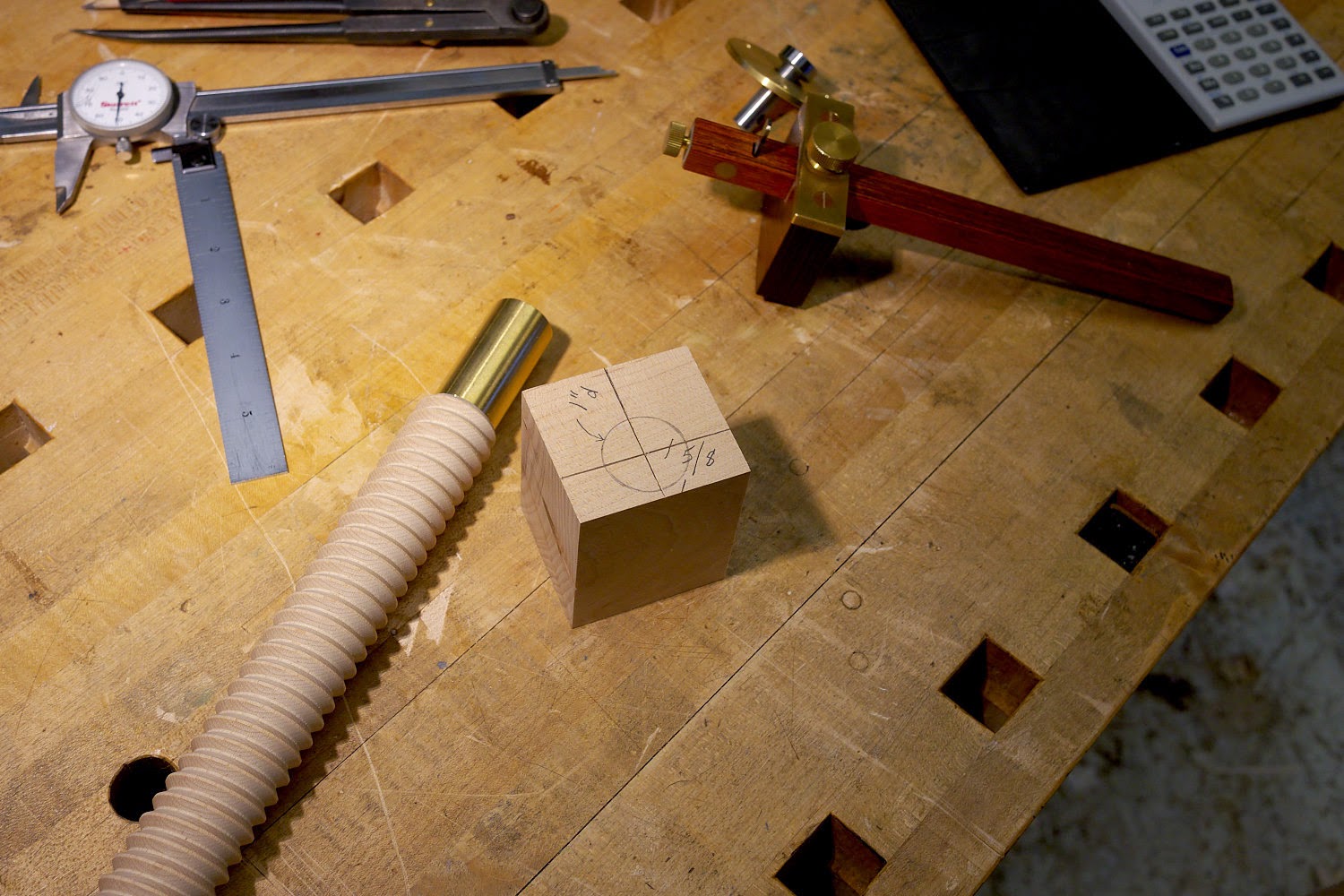

Now scribe a center line perpendicular to the other lines in the middle of the block (it doesn't have to be exactly in the middle) and carry the line down the front of the block.

Now scribe a line 5/8" up from the bottom of the block on the front side and draw a 1" circle where it intersects. This is the hole for the screw's tenon.

Where the center line intersects the line on the top of the block you'll drill a 3/16" hole.

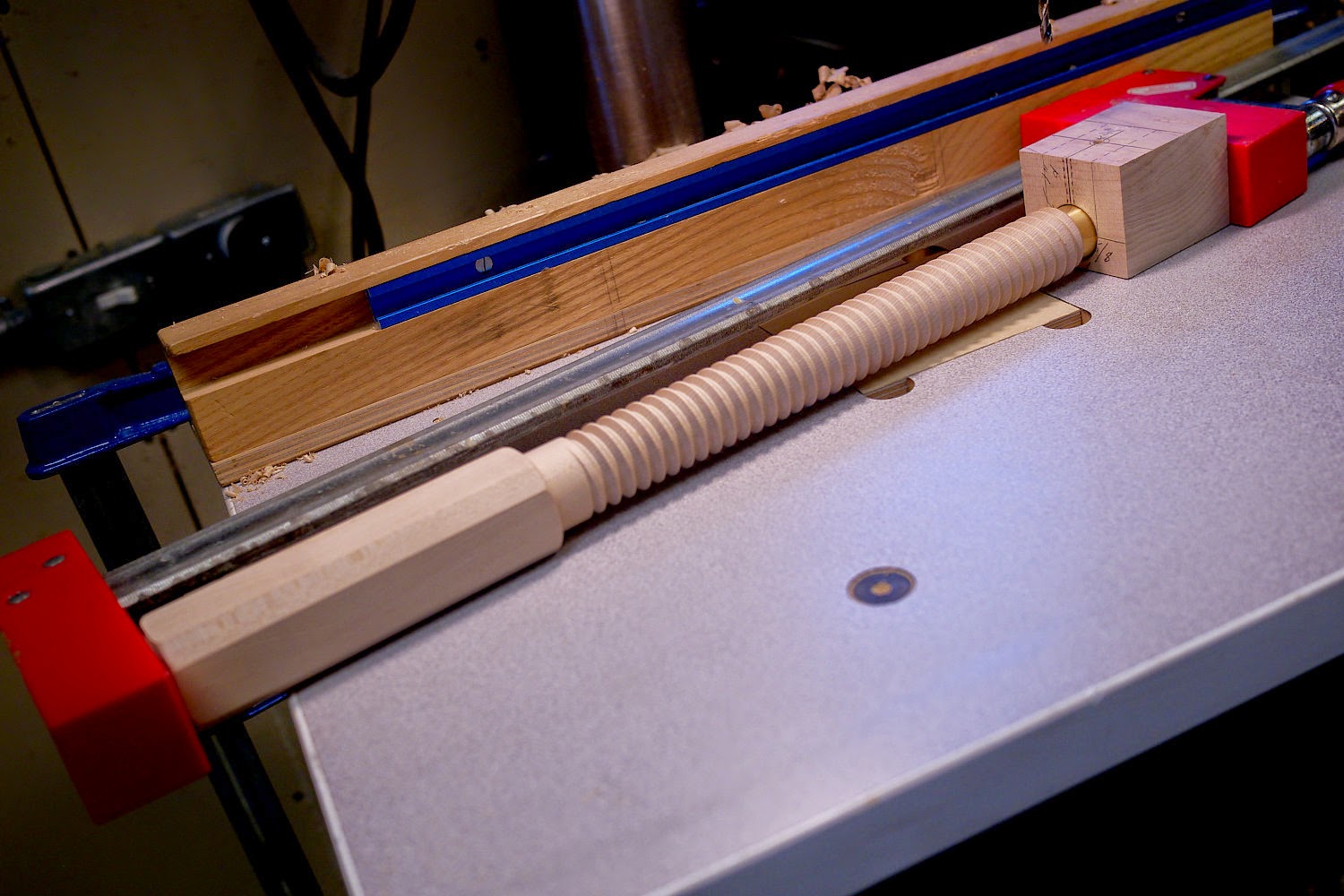

If you have a 15/16" forstner bit, mount it in your drill press. A brace and bit works too. Otherwise, use a 1" bit. Set your depth stop so the bit stops at the second scribe line on the top of the block.

Now flip the block so the top is up. Using a brad point bit, drill the 3/16" hole until you feel it break through into the larger hole.

If you drilled a 1" hole, you'll need to wrap some masking tape around the ferrule to take up the slack. Put enough layers so it fits snugly into the hole.

Hold the screw firmly into the drilling block with a clamp and drill the 3/16" hole through the guide block, ferrule and screw tenon. Use a regular twist bit, and use a sharp one.

Assemble the components and see how they all line up. The cross hole in the ferrule, screw tenon and garter pin should all line up, with about 20 thousandths play about the garter.

To test fit the groove pin in the garter pin, cut the drilling block in half and use it to support the end of the screw. Do this without the garter in place, then remove the pin. Later, when the vise is totally finished, you'll install the garter after the screw is threaded through the nut block.See video below.

If you've messed up somewhere and the garter is too tight, you can file and/or sand the end of the ferrule and tenon to loosen up the fit. If the fit is too loose or sloppy, you may be able to place a washer on the garter pin's shaft between the head of the pin and the garter. This will get buried in the moving jaw, so you'll never see it.

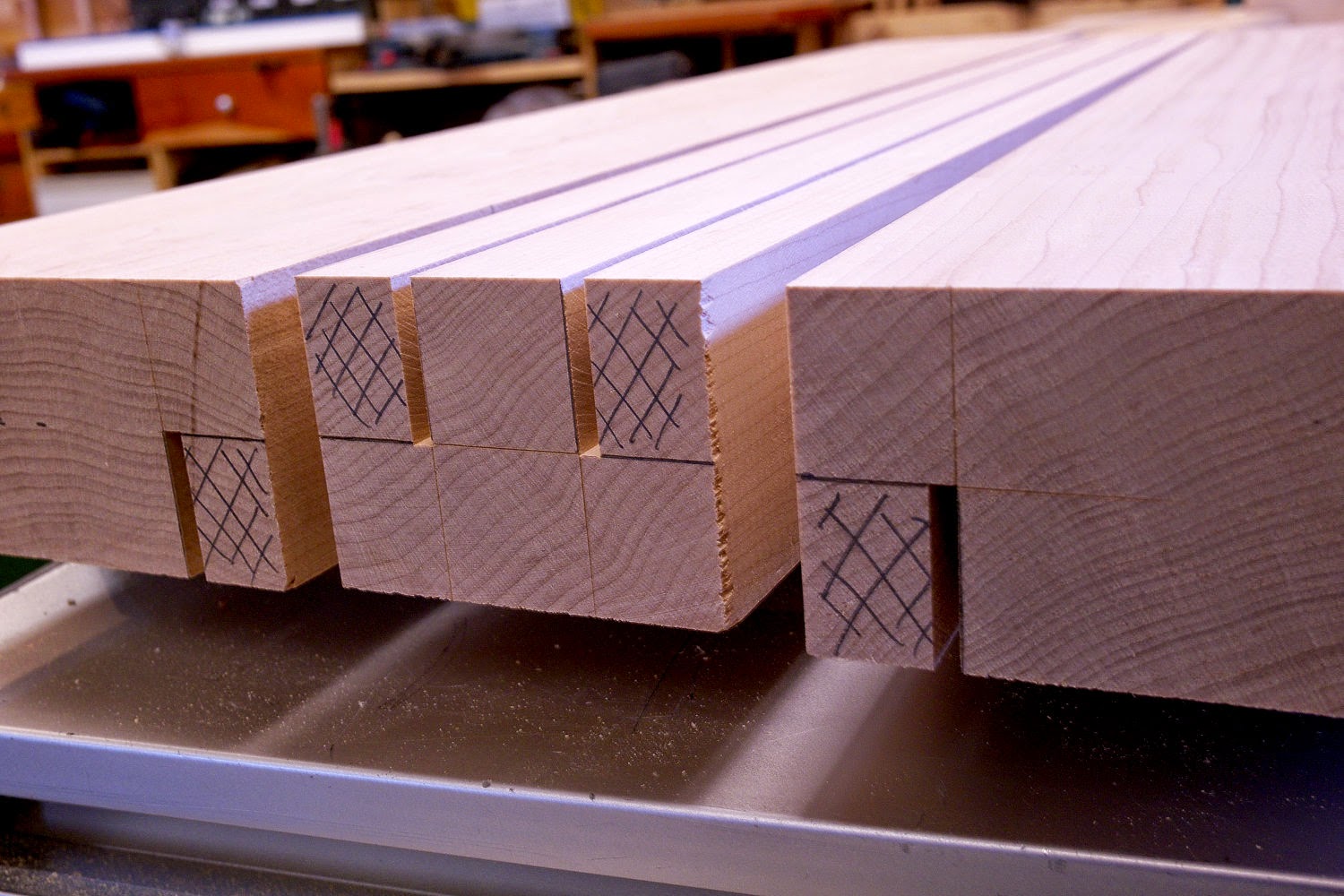

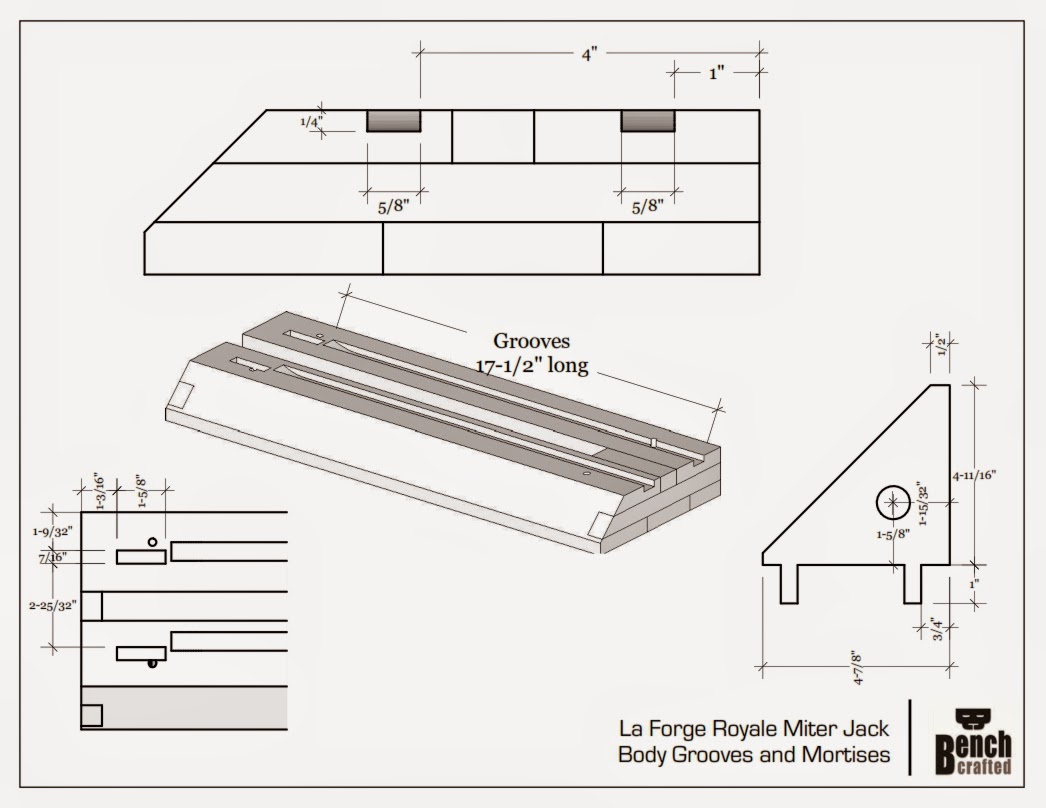

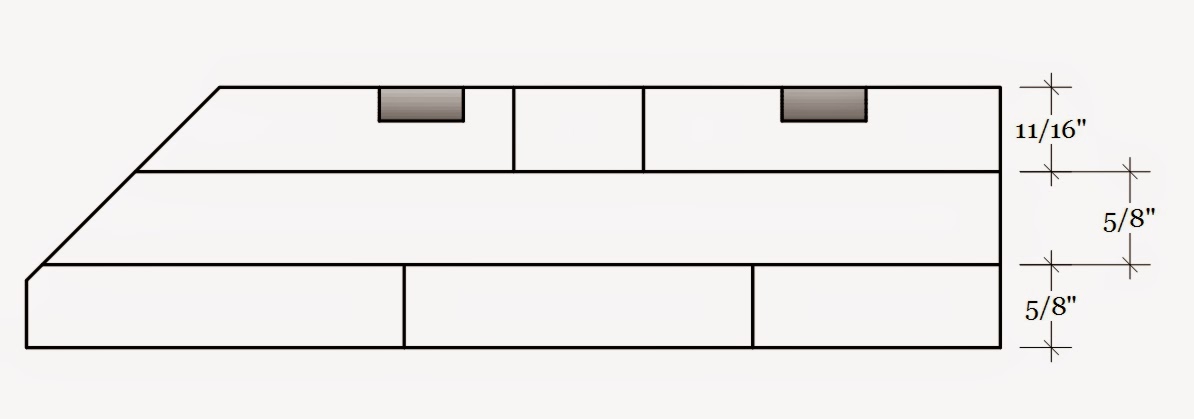

Next, lay out the joinery on the nut block. The tenons on the original are 7/16" wide, but if your tooling is happier with 1/2" feel free to use that. I'm trying to make mine as close to the original as possible, so I'm using 7/16". The grain here is running vertically. The threaded portion of the nut should be facing in. You'll also note that the nut block is a bit oversized in length and width, but not in thickness.

Also lay out the grooves for the runners on the top of the body and the end.

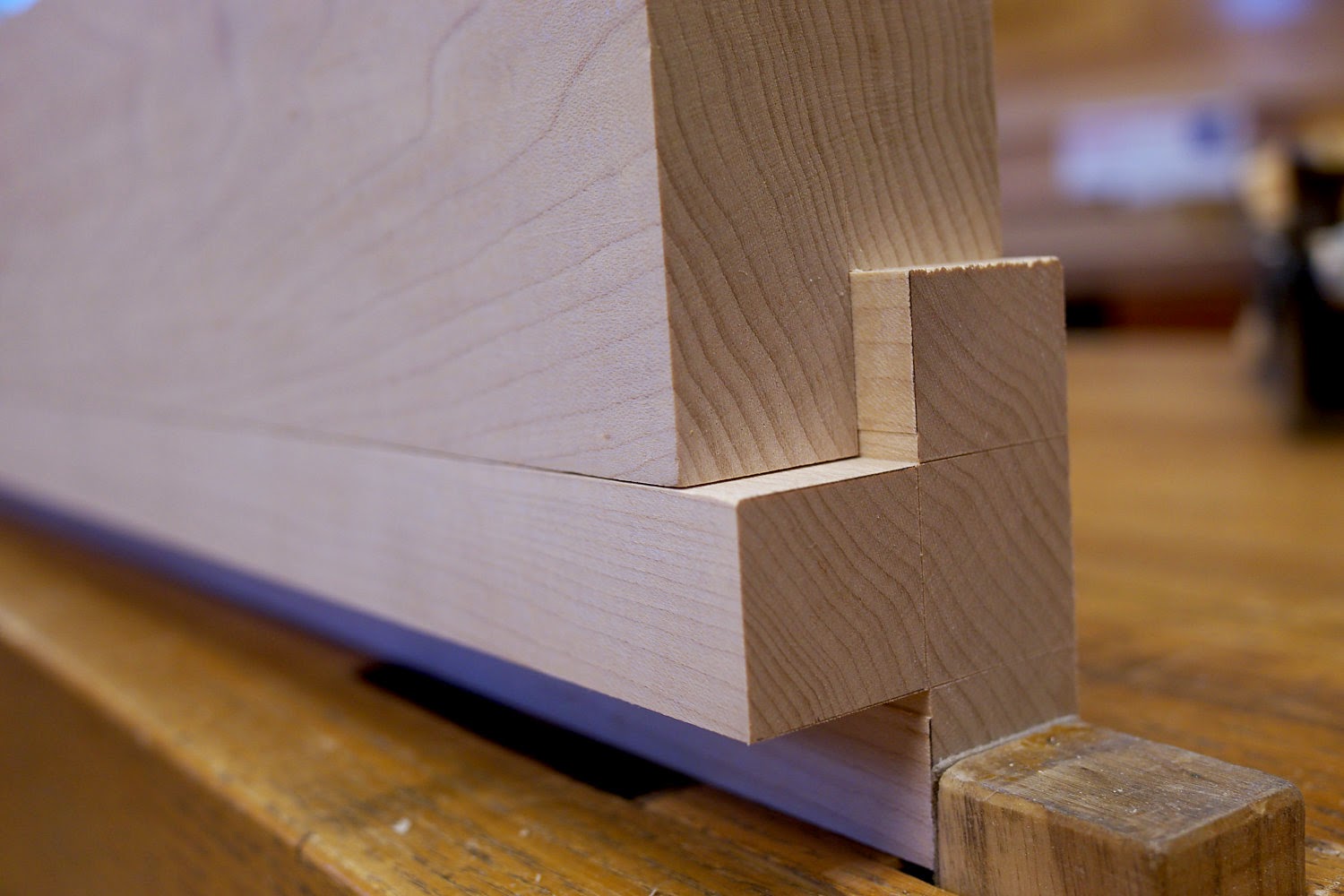

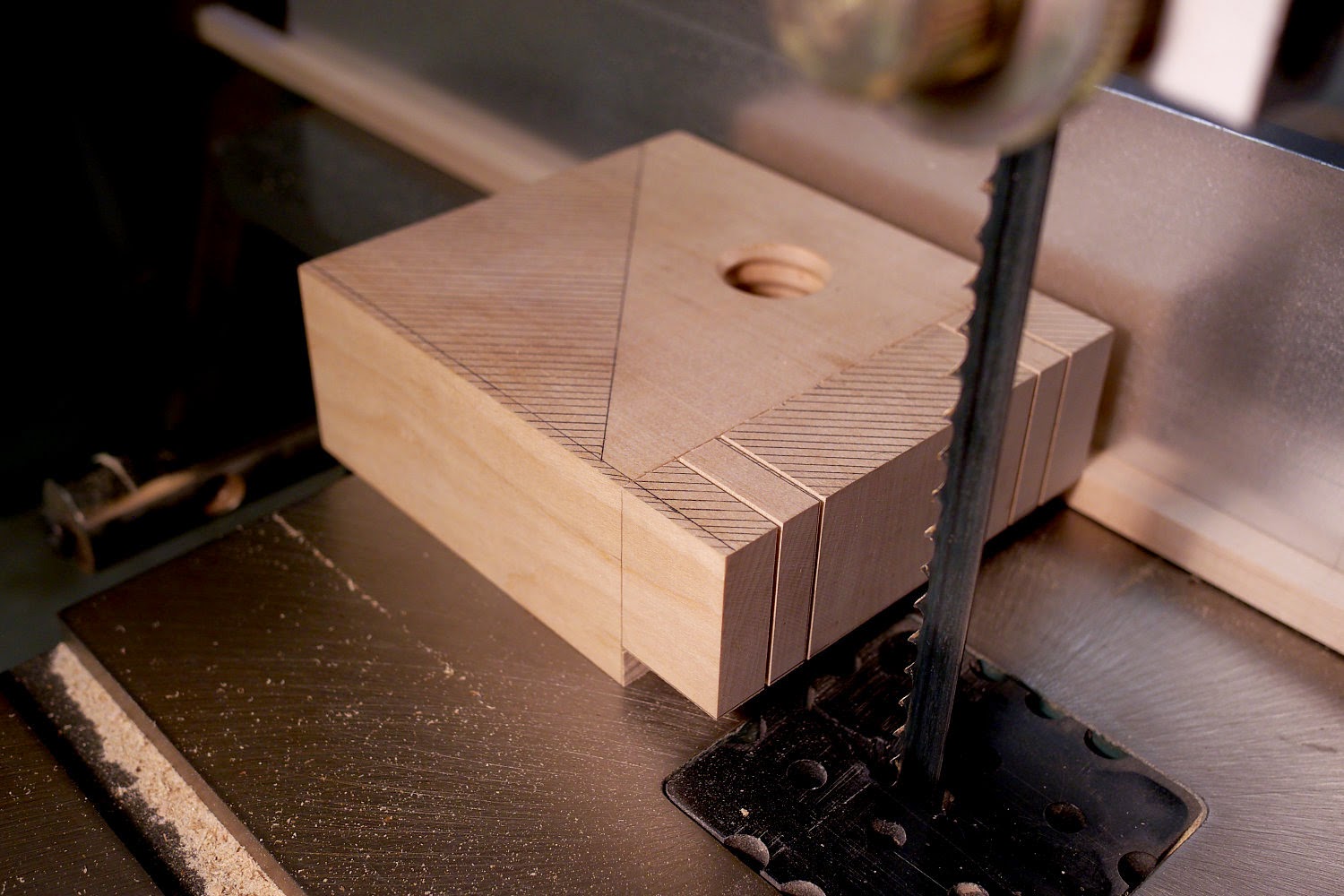

I cut the tenons on the nut block with machines and by hand. The cheeks were cut on the bandsaw. I cut the majority of the waste between the tenons freehand, getting as close to my scribed shoulder line as I dared.

The shoulders are chopped with a chisel placed directly in the scribe line. On the outside shoulders I only chop down one blow, then turn the block and repeat on the adjacent face. It's nearly impossible to chop flat to two adjacent surfaces, even with scribe lines. So I use this method.

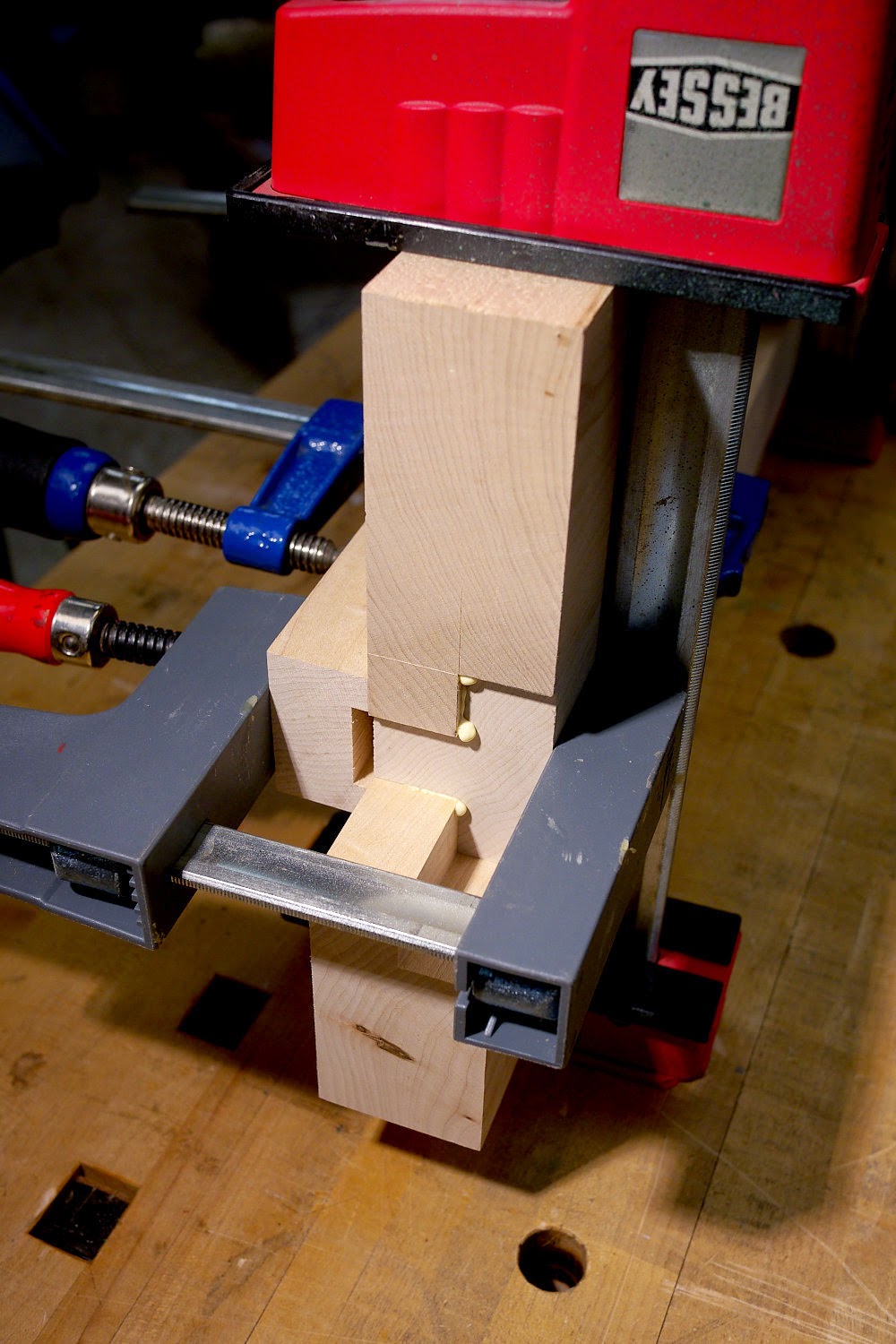

Once I've chopped down on all three sides I mount the workpiece vertically in a high vise which places the work at chest height where I can use my paring chisel to shave the remaining waste flat to the chopped areas.

I can exert lots of controlled pressure using my high vise. It's awesome. If you have the means, I highly recommend picking one up.

The trick to paring waste like this is to take small bites with the edge of the chisel. I do about half the waste, then start from the opposite side to balance wear on the tool.

Here's the video on drilling the ferrule and tenon.